The Monomyth as Interior Quest and External Reckoning in Toni Morrison’s Home

“We can train ourselves to respect our feelings and to transpose them into a language so they can be shared. And where that language does not yet exist, it is our poetry which helps to fashion it.”

“Now that my ladder’s gone, I must lie down where all the ladders start In the foul rag-and-bone shop of the heart.”

In multiform ways, Toni Morrison’s Home parallels The Odyssey. After a pointless, protracted Trojan war, the battle-weary Odysseus ranges across the Aegean on his way home. He is beset by enemies and evils and, as in most quest tales, the hero must use his wiles to negotiate perils, overcome trials, and fight monsters to return home, a changed man. Home’s Frank Money quests through a segregated country after his own psychic fracturing as a black soldier in the “forgotten” war with Korea. Like Odysseus, he longs for hearth and home and his quest involves the rescue of a woman, in Frank’s case his fragile sister Cee, and the reintegration of his damaged heart and mind. The novel is structured, like many of Morrison’s novels (and like Joseph Campbell’s monomyth itself), as a circular hero’s journey. But Morrison’s story is shaped more like a spiral or gyre than a circle, for the physical journey across a hostile American landscape is accompanied by an inward journey from an “outside” characterized by the jagged, broken fragments of the hero’s life to the painful center of his psyche—the space where he can finally incorporate outer and inner.

The home Frank seeks is less a physical space than a psychological one. Morrison employs and complicates the structure of the ancient epic in order to challenge the linear storytelling, linear history, linear ideas of progress, and other discourses of linearity so prevalent in the white Western world (and so suppressive of other epistemological modes)—forms it has used to commit atrocities against its cultural “others.” Living black in a racist country that obfuscates its racism with fraudulent national narratives, she implies, prevents healing for the black American. In this spiralized hero’s journey, “home” is a space of self-definition, a reconnection with earlier modes of healing (such as ritual) and a space where witnesses help reclaim a hijacked personal narrative. In a sense, Morrison’s novel is metafictional in that it models how stories themselves are a form of healing, especially when they act as crosscurrents to damaging dominant narratives that contribute to ongoing trauma.

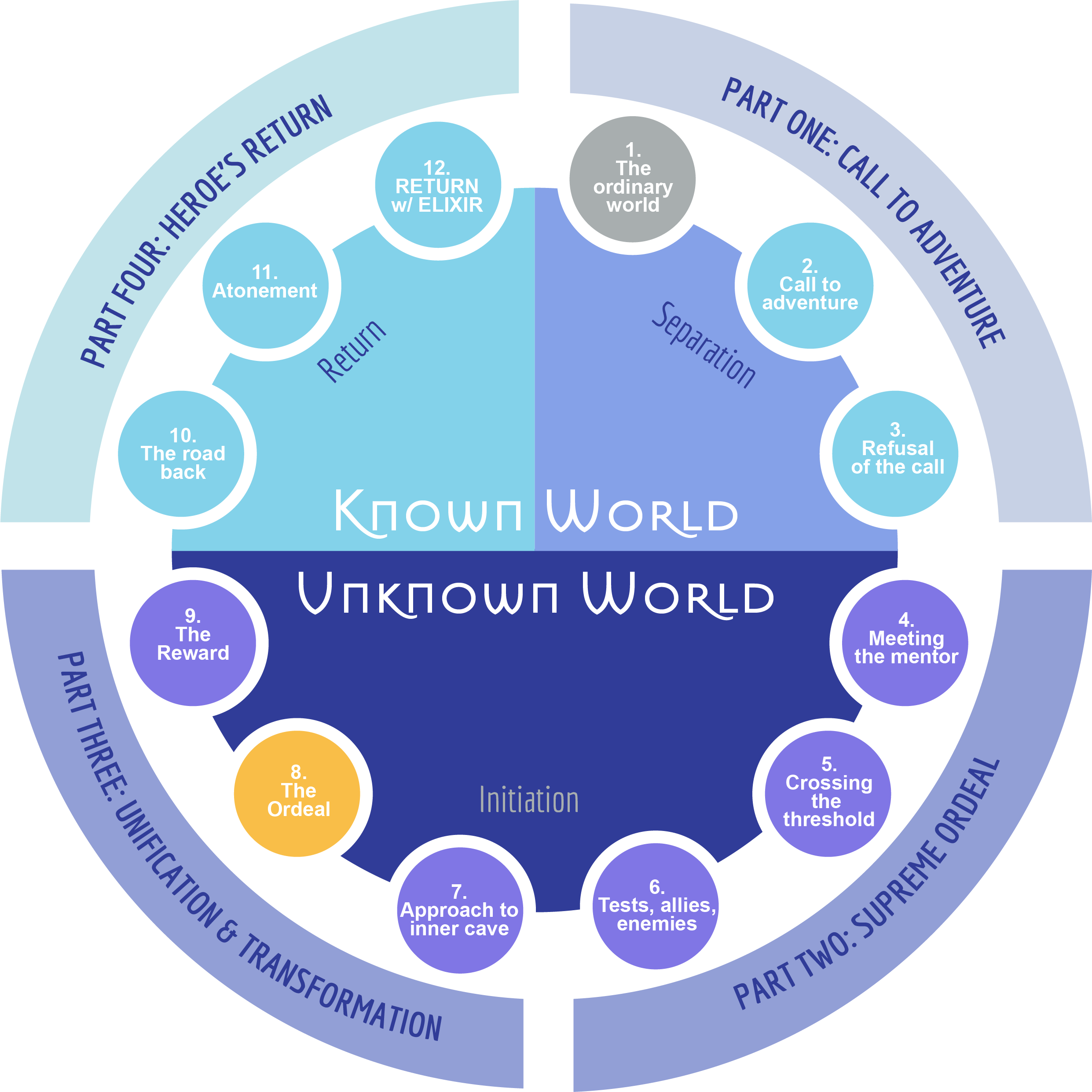

Home as a Hero’s Journey

In The Hero with a Thousand Faces, Joseph Campbell explores the archetype of the “hero’s Journey,” and the way epics such as The Odyssey engage similar themes of transformation and arrival all over the world. He envisions this monomyth as a shared human patrimony, a vast subterranean river of human experience, from which all creativity is drawn, and “through which the inexhaustible energies of the cosmos pour into the human cultural manifestation.” Indeed, he believes that all mythology is “the same, beneath its variety of costume.” The first stage of Campbell’s circular hero’s journey is the “call to adventure” (Campbell 1-2, 28). Home begins with Frank Money, rambling at loose ends a year after his discharge from the army where he fought the United States’ war with Korea. He suffers PTSD. He is tortured by flashbacks and hallucinations and is consequently prone to alcohol abuse, to quiet the noise of the war, and his blackouts get him into trouble. One such event has landed him in hospital, drugged and chained to a bed, and that is how we find him at the opening of the novel’s events. A savvy reader might note that Odysseus, too, is imprisoned and in thrall on Kalypso’s island at the commencement of The Odyssey. Morrison has deliberately placed Frank in a mythopoetic space. The narrative reveals that he has just received what could be thought of as “the call to adventure:” A letter from a stranger, simply saying, “Come fast. She be dead if you tarry” (Morrison 8). We don’t know who “she” could be nor whom the note is from, but it spurs our hero to action, urging him to escape the hospital, as a visit from a messenger god might do in an ancient epic.

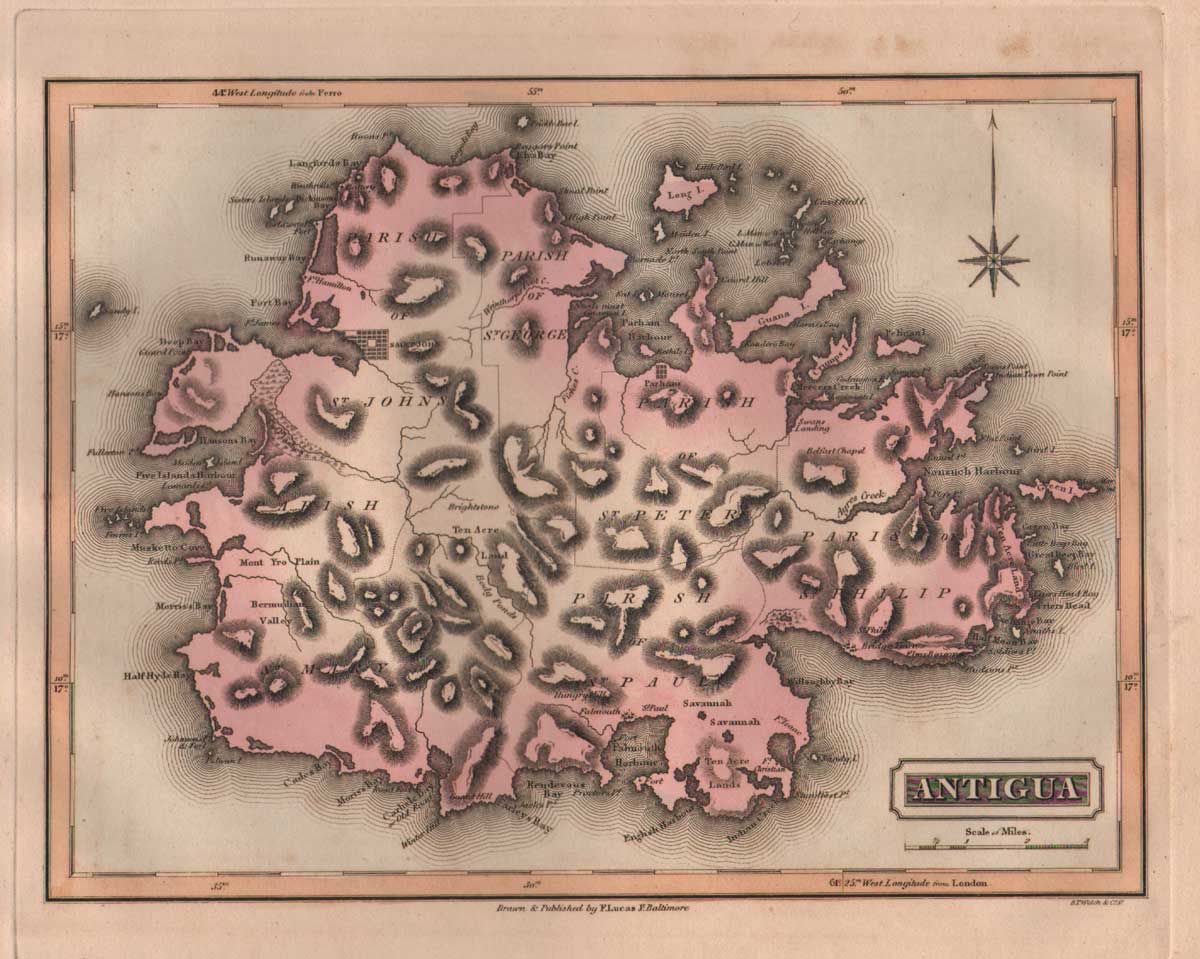

Nor do the resonances between Home and Homer’s epic stop there. The Odyssey’s capricious gods are in Morrison’s novel represented by the “tyrant-monsters” of American racism and capitalism: Frank must journey across a hostile land full of random police violence, murderous racists, the ever-present need for money to travel and keep oneself alive, and the demons in his own soul. The second thread to Homer’s epic is Penelope, the woman who has been left behind to keep the household, and she has an analogue in Morrison’s tale too. Ycidra (“Cee”) is still rather close to their hometown of Lotus, Georgia (a town Frank joined the army to escape, for the “fifty or so houses and two churches” do not feel like home for him), where she waits. When we first meet her, she is bemoaning her abandonment on multiple fronts, by a faithless husband, a villainous grandmother, and a brother too damaged to return. Cee is naïve and fragile in her own estimation, and we see that even she knows that Frank’s rescue might not be in her own interests, for she tells herself that “where her brother had been, she had no defense. That’s the other side, she thought, of having a smart, tough brother close at hand to take care of and protect you—you are slow to develop your own brain muscle” (Morrison 48). Her life is marked by waiting, just as Frank’s is marked by his inward/outward journey. Like it does with Odysseus and Penelope, the narrative nudges them toward one another. But it is not until Cee undergoes a harrowing trauma at the hands of a doctor whose evil smacks of Josef Mengele that the hero is finally jolted out of his self-involved stupor to initiate the quest. This, we discover, is the letter that calls him to action.

In “Flying Home: A Mode of Conversion in the African American Context,” Jay-Paul Hinds discusses the introduction of African folklore to a literature rife with Eurocentric epic traditions, and its specific emphasis on African and African-American journeys being necessarily roundtrip. Joseph Campbell writes of universal themes, and these are not contradicted but rather refined or made more specific by Hinds. He writes of the “canon of latent folktales that modern writers are attempting to bring back to African American consciousness,” in which the hero escapes his suffering by flying away, and then, struck by conscience, returns home armed with supernatural aid to help those still suffering. Home is full of this kind of circle, albeit metaphorical rather than supernatural—a desire to escape, followed by a wrestling with virtue and a final resolve to return to help those still in need. As Hinds notes, “flying is a mode of religious conversion… that has enabled African Americans to come in touch with supernatural resources during times of sociopolitical, communal, and personal sorrow” (383). Morrison engages the European epic but inflects it strongly with African folkloric modes in order to model a hybrid form of healing that black Americans can use to repair themselves and one another after centuries of systemic sociopolitical damage. Frank has been to war, and war is traumatic, but his return to a racist country after serving in an integrated army means he is cut off from the healing resources available to other veterans; Cee is traumatized by an act of purposeless violence to her body, but the fact the violence is perpetrated by an authority figure whose job it is to care for the vulnerable renders her voiceless. It is no wonder that the European hero’s journey is here leavened with African storytelling tropes: Dominant narratives do not provide language enough for these heroes to give voice to their sorrows.

Maxine L. Montgomery discusses the trauma caused to black soldiers in the “forgotten war” between the United States and Korea in “Re-Membering the Forgotten War: Memory, History, and the Body in Toni Morrison’s Home.” She focuses in particular on the way it was compounded for black soldiers when they were forced to reintegrate into a hostile, racist America after the war—a different America from the one encountered by white soldiers. At the outset of the novel, Frank is grappling with his PTSD alone. He, and other black soldiers, are doubly traumatized by the hostility of a country that is happy to use them to fight abroad but leaves them alone to suffer appalling racism at home, often at the hands of those in power. According to Montgomery, their experiences with racism after the war made recovery from the trauma of it well-nigh impossible. Further, she argues that Home endeavors to expose the fraudulent narratives of the whole decade: “Morrison's comments about the need to ‘rip the scab off’ of the 1950s,” says Montgomery, “suggest the authorial effort to excavate obscure moments in our national history, reconstructing them from the vantage point of the marginalized subjects who witnessed those events firsthand” (322). Frank suffers alone; Cee, protected her whole life by her brother, does not know how to resist the white doctor who acts as though he has her best interests at heart, and then secretly sterilizes her while she is under his employ. Morrison’s heroes do not really have a home in America to return to: Their job, we learn, is to create one in their hearts and for each other.

So, Morrison complicates her European epic by chronicling experiences that are largely erased by a Western literary canon—a canon that rejects texts that don’t support its metanarratives. Her hero’s journey demonstrates the horror of being an American “Other,” having at every turn to negotiate with an American superstructure whose foundations have racism holding its masonry together (if I’m not overtaxing the metaphor). Campbell conceives of the traditional hero’s journey as circular in shape. Morrison uses this template but subverts a Eurocentric schema with characteristic narrative virtuosity: By making the journey a spiral that leads inward at the same time it moves across/around, she demonstrates how to access and speak the “unspeakable.”

The Hero’s Journey of the Heart: Healing as Inward Spiral

Morrison’s “excavations” (to borrow Montgomery’s word), especially as regards speaking the unspeakable, correspond to Judith Herman’s thesis in Trauma and Recovery; the tripartite model of the subconscious as conceptualized by Jacque Lacan; and, at the macro-level, Jean-Francois Lyotard’s theories of postmodernism, in particular his “incredulity toward metanarratives” and the concept of greater truth embodied in petit récits. Herman’s work on trauma elucidates the project of Morrison’s novel, and perhaps informs it (if only by osmosis). One of its foci is the behavior of the world surrounding the victim. Herman argues that bystanders faced with another’s trauma do whatever they can to avoid identifying with it, especially if they suspect their own complicity in its cause. The America in Morrison’s novel violently rejects the harm it has caused black people. “When the traumatic events are of human design…” writes Herman, it becomes “very tempting to take the side of the perpetrator” (7). Frank must overcome American narratives with as much vigor as he must overcome American violence. And the narrative Frank encounters most often is that despite America’s conception of itself as being a bastion of human rights—for such was its pretext for war in the 20th century—he is unwelcome and homeless in the land of his birth and nationality, despite his sacrifice overseas. These narrative inconsistencies are compounded, moreover, by the fact that his role in the army was a reversal of his role as a citizen: In Korea he was a powerful aggressor, even a colonizer, while stateside he is an abject victim. Montgomery notes that the novel’s structure—a structure that includes a framing metaphor, resolved at the end; an inward journey that parallels the outward one; and testimonials from multiple interested parties, including two from different aspects of Frank’s psyche—is “designed to correct the troubling omissions in extant historical record” (326). Before the book’s events, there is the sketchy, impressionistic account of white men burying a black man alive, witnessed by Frank and Cee. We do not discover its significance until the end of the book, when the two are finally ready to confront and, literally, exhume the past. During his journey to find Cee after his discharge, Frank encounters black trauma and black coping strategies wherever he travels, and his psyche accumulates these strategies over time. Unlike Odysseus, Frank is not the exemplar of his culture but a stranger in his own land, accepting help from a kind of underground railroad of other marginalized Americans, and taking healing where he can get it, but persecuted at every turn and prone to violent fits of rage. Cee, too, has to negotiate a hostile world. When she is hired to clean the kindly Dr. Beauregard Scott’s office, she laments that she cannot understand the books on his bookshelf, but Morrison makes sure the reader can: “How small, how useless was her schooling, she thought, and promised herself she would find time to read about and understand ‘eugenics.’ This was a good, safe place” (65). We feel the horror of Cee’s innocence and we know before she does that the kindly doctor has evil designs. But there is no national narrative that informs about the forced sterilizations and other horrendous medical experiments of the era conducted on the bodies of black Americans without their knowledge or consent. Herman notes the difference in available narratives between the trauma of those with cultural capital as compared with those without:

Soldiers in every war, even those who have been regarded as heroes, complain bitterly that no one wants to know the real truth about war. When the victim is already devalued (a woman, a child), she may find that the most traumatic events of her life take place outside the realm of socially validated reality. Her experiences become unspeakable (8).

The white American narrative renders Frank and Cee’s experiences and trauma unspeakable, and this compounds the damage, forcing them to create their own spaces for healing through community, ritual, and the ritual reframing of their own stories. That they find a way to heal themselves in a hostile world of murderous and dehumanizing racism offers a corrective to older epic modes: This, contemporary readers note, is the definition of true heroism.

In “Symbol and Language,” Lacan’s theories of the unconscious provide a helpful visual frame for Herman’s concept of trauma. He imagines the unconscious as composed of three interlocking circles, representing the “symbolic,” the realm of language, the “imaginary,” the world of dreams and images, and the “real,” which is the unspeakable heart of us, where interior pain without a narrative can be expressed only as symptom (Lacan 171-2). Herman asserts that the biggest obstacle to healing is the refusal of others to bear witness to an individual’s trauma, for it’s so scary to be confronted with a chaotic world and/or to be implicated in another’s pain that it is often easier to identify with the perpetrator than the victim, which is anathema to the victim’s healing. This builds off Lacan’s contention that healing is the transfer of the “real” (the unspeakable) to the “imaginary” and the “symbolic.” In an early episode in Home, Frank is speaking to the Reverend John Locke, who is the first in the novel to put words to an unspeakable reality: “‘You go fight, come back, they treat you like dogs. Change that. They treat dogs better’” (Morrison 18). This is the novel’s first transference of the real to the symbolic. In a later episode in the book, Frank stops in a jazz club and witnesses a kind of “speaking the unspeakable” through music: “After Hiroshima, the musicians understood as early as anyone that Truman’s bomb changed everything and only scat and bebop could say how” (Morrison 108). This encounter can be seen as a transfer of the unspeakable into the imaginary space of music. Frank’s drinking and violence and nightmares, meanwhile, are the symptoms that do not heal him. He survives on the scraps of healing he encounters until he has enough inner resources to face himself. Cee’s naivete and credulousness are symptoms, while her friendship with the Scott’s maid, Sarah—who, it is later revealed, sends the note to Frank that is the novel’s precipitating event—is her first inkling of her own value, a first step in the process of self-reclamation through the imaginary that must continue later in the book. Sarah’s willingness to stand up to the doctor so that Frank can carry a critically damaged Cee out of his office demonstrates the indispensability of allies who see and recognize unspeakable trauma. Morrison’s novel forces Frank and Cee face-to-face with their pain so they can move their unspeakable “real” into the realm of the symbolic through language and a narrative (as in Frank’s case); and into the realm of the imaginary through ritual and self-reliance (as in Cee’s case).

Lyotard is notoriously difficult to parse, but instructive in revealing the larger superstructural conditions that give rise to the trauma of marginalized citizens. Morrison engages some of his theories of postmodernism, which, in The Postmodern Condition, Lyotard defines as a studied “incredulity toward metanarratives” (8). Where Herman and Lacan form the basis of an individual’s healing, Lyotard is concerned with the relationship between power and reality, and he examines these phenomena on the national and cultural scale. He argues that metanarratives or “grand narratives” always, by definition, serve the interests of the powerful at the expense of the marginalized. Herman discusses the consequences of this, for “The more powerful the perpetrator, the greater is his prerogative to name and define reality, and the more completely his arguments will prevail,” and so, in her estimation,

The systematic study of psychological trauma… depends on the support of a political movement… The study of war trauma becomes legitimate only in a context that challenges the sacrifice of young men in war. The study of trauma in sexual and domestic life becomes legitimate only in a context that challenges the subordination of women and children (8-9).

To promote the dismantling of grand narratives, Lyotard proposes the aggregation of “petit récits,” or “little narratives,” in which all stakeholders in history add their story, even (or especially) if it contradicts the grand- or metanarrative of the nation or culture, or if it emanates from those with limited power within the system. The more limited the subject’s power, Lyotard argues, the more we should aim to amplify her story. He proposes wresting the story from the “authorities” in order to refine “our sensitivity to differences and [reinforce] our ability to tolerate the incommensurable. Its principle is not the expert’s homology, but the inventor’s paralogy.” (Lyotard 37-8). I argue that Morrison’s project is exactly this kind of petit récit: She is an inventor extraordinaire, modeling a paralogical method of healing in the face of a rigid, self-perpetuating “reality-logic” crafted, maintained, and jealously guarded by the dominant culture.

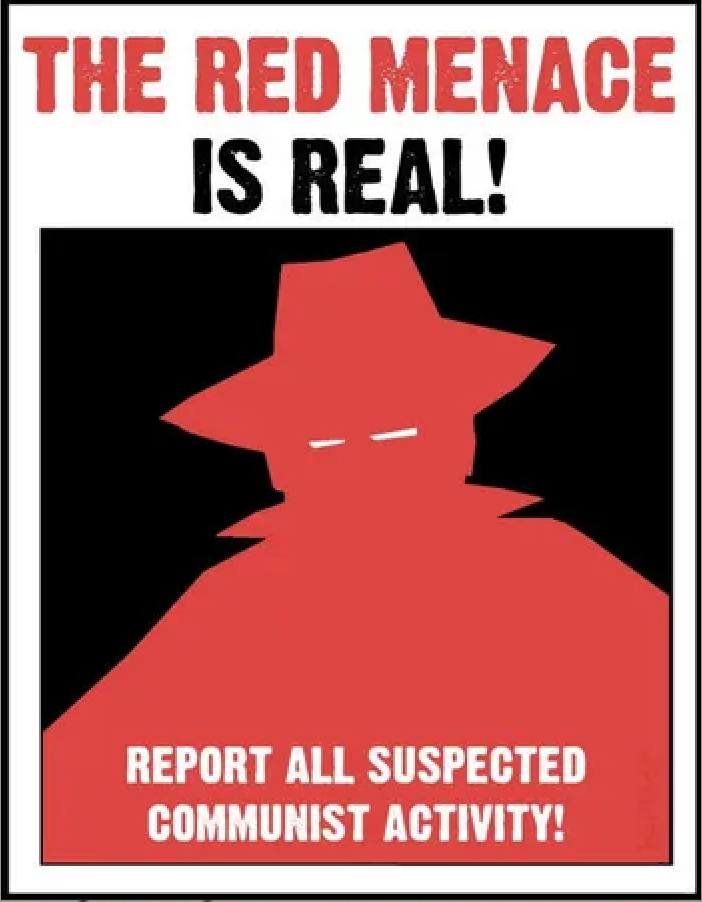

Donald E. Pease explicates the specific paradoxes of the 1950s American narrative in his article “The Uncanny Return of Settler-Colonial Capitalism in Toni Morrison’s Home,” in which the contradictory messaging of postwar rhetoric is made doubly unheimlich for the black returning soldiers who are forced to occupy the no-man’s-land between rhetoric and reality. Pease discusses Morrison’s omissions of Cold War philosophy, and the way her omission highlights the contrast between propaganda and fact:

Morrison confronts readers with a comparably uncanny experience when she deletes from the narrative any trace of the Cold War ideology whose structures of feeling, epistemologies, and military architecture the Korean War was putatively fought to establish… After the newly formed Department of Defense described the United States as an anti-racist state charged with safeguarding liberal humanity from “Communist slavery,” racial desegregation emerged as an essential component of the U.S. effort to win the hearts and minds of populations in Korea and across the decolonizing world (Pease 50).

But of course the reality of American racism in the 1950s belies this propaganda in uncanny ways, and black veterans must navigate the wide gap between them as yet another obstacle to overcome. Morrison’s decision to elide the “polarizing dichotomies sedimented within the Cold War frame” shines paradoxical light on them while also “disintersecting race from other articulations of power” and shuttering “the white supremacist gaze that would have employed these perspectives to place Frank under the control of the carceral state” (Pease 53). Morrison’s choices are self-conscious, as she makes plain in an interview for Interview magazine:

Was that what [the 1950s] was really like?… it tends to be seen in this Doris Day or Mad Men-type of haze… Somebody was hiding something—and by somebody, I mean the narrative of the country, which was so aggressively happy… And I kept thinking, This kind of insistence, there’s something fake about it (qtd. in Pease 50).

So, contending with national lies and interior disquiet, Frank’s journey leads him from Seattle to Georgia on a rescue mission, but it also leads him closer and closer to a truth that is central to him and his unspeakable “real.” For Frank, too, is “hiding something.” It is the voiceless lacuna at the center of the spiral into his psyche, and it drives his rescue mission, his drunk blackouts, the fights he gets into, and everything else, until he can finally admits it to himself.

The narrative takes its time zeroing into this central truth. Morrison structures his narrative in two strata: A third-person omniscient narrator tells the story of Frank that the world sees, but a parallel first-person, present tense, stream-of-consciousness monologue occasionally intrudes on the third person narrative, sometimes chastising or contradicting it:

Korea.

You can’t imagine it because you weren’t there. You can’t describe the bleak landscape because you never saw it. First let me tell you about the cold. I mean cold. More than freezing, Korea cold hurts, clings like a kind of glue you can’t peel off (93).

Slowly this narrative corrects the other, more rehearsed one, in the psychomachic manner of a man debating himself. In this space, Frank tells us of the little Korean girl who foraged for garbage to eat left behind by the soldiers. As she forages one day and Frank observes a soldier confronting her as she holds a rotten orange. She “reaches for the soldier’s crotch, touches it. It surprises him. Yum-yum? As soon as I look away from her hand to her face, see the two missing teeth, the fall of black hair above eager eyes, he blows her away” (Morrison 95). This revelation comes three quarters of the way through the novel and coincides with a lessening of nightmares and hallucinations for Frank: His ability to put words to the trauma begin to move his experiences and guilt from the realm of the real to the realm of the symbolic.

The Round-Trip Flight: Metafictional Collectivity

Frank and Cee go to Lotus, the final stop in their odyssey. What happens there comprises the “home” of the novel’s title, but it is also operating on a metafictional level, modeling a way to approach trauma and recovery for marginalized people whose stories might be outside of officially-sanctioned reality. When they arrive it is not yet clear whether Cee will survive the experimental surgery performed on her by Dr. Scott. But the town closes around brother and sister in ways they were not expecting and comes to represent the community that traumatized people need to heal. Cee is whisked away to recover while Frank does odd jobs here and there to keep himself busy. Contrary to his memories of it, the town has grown benevolent in his estimation:

It was so bright, brighter than he remembered. The sun, having sucked away the blue from the sky, loitered there in a white heaven, menacing Lotus, torturing its landscape, but failing, failing, constantly failing to silence it: children still laughed, ran, shouted their games; women sang in their backyards while pinning wet sheets on clotheslines; occasionally a soprano was joined by a neighboring alto or tenor just passing by (Morrison 117).

We see contemporary trauma therapy at work in Frank’s recounting of trauma throughout the novel, the apotheosis of which occurs in Lotus. And we see it in the healing rituals practiced by the women who aid in Cee’s recovery, for a group of local women take immediate, unsentimental control of Cee’s healing, and every woman in the neighborhood bands together to prevent Frank from seeing his sister for two months. When they allow him entry, “Two months surrounded by country women who loved mean had changed her. The women handled sickness as though it were an affront, an illegal, invading braggart who needed whipping” (Morrison 121). They express scorn toward the patient and handle her ungently. They force her to engage in “sun-smacking,” which meant “spending at least one hour a day with her legs spread open to the blazing sun. Each woman agreed that that embrace would rid her of any remaining womb sickness” (125). She is skeptical of the ritual, but she recovers, and after she recovers, the women grow gentle. One of them tells her, “‘Nothing and nobody is obliged to save you but you… Don’t let… no devil doctor decide who you are. That’s slavery. Somewhere inside you is that free person I’m talking about. Locate her and let her do some good in the world” to which Cee replies, “I ain’t going nowhere… this is where I belong” (Morrison 126). According to Herman, a community willing to bear witness but also to allow the survivor to wend her own way toward recovery is key to healing trauma. Since “the core experiences of psychological trauma are disempowerment and disconnection from others,” then the survivor needs to establish new connections, and then needs to find her own story: Indeed, “The first principle of recovery is the empowerment of the survivor. She must be the author and arbiter of her own recovery” (Herman 133). Frank wants to save her like he always has, so the women drive him away and teach her self-reliance. Ultimately, it is Cee, with the scales of naivete fallen from her eyes and a new, fledgling sense of herself as the agent of her own saving, who rescues him, though she never knows it.

For Cee has come to understand something about her relationship with Frank: “While his devotion shielded her, it did not strengthen her… she wanted to be the one who rescued her own self.” When she openly weeps in front of him, she then refuses the “don’t cry” he always gives her when she is suffering, answering, “I can be miserable if I want to… I’m not going to hide from what’s true just because it hurts” (Morrison 129-131). Her resolve, and her grief, and her bravery in facing the child she can never have who haunts her dreams, inspire him to finally face the black hole within him. For he, too, is haunted by a child. He confesses to himself, or to his chronicler, in the italics reserved for his interstitial corrections:

I have to say something to you right now… I lied to you and I lied to me…

I shot the Korean girl in the face.

I am the one she touched.

I am the one who saw her smile.

I am the one she said “Yum-yum” to.

I am the one she aroused (Morrison 133).

Frank has been experiencing a dissociation from events common to combat veterans. Herman notes that in combat it is

not merely the exposure to death but rather the participation in meaningless acts of malicious destruction that rendered men most vulnerable to lasting psychological damage… [many soldiers] admit to committing atrocities that haunt them, with which they bludgeon themselves, and which prevent their recovery, since recovery requires forgiveness. These soldiers often do not want to forgive themselves (54).

After admitting the unspeakable to himself, Frank and Cee can begin to live. They are home, physically and spiritually, despite a country that endeavors to dispossess black Americans at every turn. In the final pages of the book the siblings disinter the black man they saw being buried, and they uncover the mystery of what happened to him: It was a kidnapped black father and son, forced to fight to the death, wherein the father sacrificed himself so the son could survive. He wasn’t dead yet when the white men who arranged the battle royale buried him. Morrison dramatizes the personal search for modes of healing, but the final revelation places the story in a larger context of racialized violence, and she clearly intends her novel to be read metatextually as well. Irene Vissar observes how Home is structured as a metatextual argument in “Entanglements of Trauma: Relationality and Toni Morrison’s Home.” Specifically, she notes that the theme of psychologically confronting trauma “is foregrounded in the novel by the structural device of the frame narrative: Frank, the traumatized war veteran, relates his personal story to a listener, who is the (nameless and faceless) author of his written text” (8). But when he takes back the story, he reclaims his own narrative as though it has been kidnapped (which indeed it has). The testimonial, according to Vissar and Herman, is what is used now to reconstruct and address collective trauma, like the trauma suffered by black Americans from many hundreds of years of oppression and metanarrative obfuscation. Morrison demonstrates the need for community and solidarity in recovery as well as a silent witness, and she emphasizes the crucial role of stories in the rebuilding of damaged psyches. Frank’s interstitial first-person accounts that correct for the omniscient narrator’s incorrect assumptions read like oral reclamation of written untruths, and, according to Visser, “orality and rituals function as catalysts in processes of mourning and grieving in the aftermath of traumatic events” (3). When we leave Frank and Cee, they are facing the world as agents of change themselves, committed to correcting ancient wrongs and fully responsible for themselves and those around them. They have made a roundtrip journey back to Lotus, and unlike the denizens of the land of lotus-eaters in The Odyssey, Lotus is the town where they doff their enforced forgetting and embrace their warts-and-all truths.

In “Dystopia, Utopia, and ‘Home’ in Toni Morrison’s Home,” Mark A. Tabone, like Pease, is concerned with how Morrison exposes the 1950s American utopia (still popular among American conservatives) as a dystopia: Her novel presents a “demythologizing dystopian portrayal of 1950s America,” and in her rendering “she rejects nostalgia and escapism to posit utopia not as an ideal or blueprint, or primarily as a space, but instead as concrete, and ‘endless,’ ethical practice” (Tabone 292). He connects the testimony of Frank and Cee—a process that contributes to their personal healing—with the demythologizing force of such testimony,

in which mutually exclusive versions of history are implicitly placed in confrontation in order to stress the fact that the past is not a set of established truths in which all further developments originate, but rather a contested site of cultural codes, each designed to preserve (or efface) a particular version of cultural and national identity (Tabone 297).

In other words, their petit récits fly in the face of America’s national narrative about its own history and purity. The novel is a potential model for other Americans similarly damaged by racism, marginality, violence, and trauma to help themselves and one another. Herman and Lacan are psychologists, but their theories of recovery engage aspects of narratology: Trauma therapy integrates aspects of storytelling—or rather of story reclamation. Morrison is a storyteller, but her novel integrates many aspects of psychology, so much so that the book itself becomes a kind of survival manual for dealing with systemic problems and a political and economic landscape that has virtually no interest in personal psychological health. By setting her story at once in a specific place and time in American history but also engaging aspects of Campbell’s monomyth, she universalizes a method of building identity and course-correcting an off-the-rails life in a world beset by angry, capricious, and unjust gods, even if those gods are your own country’s government, citizens, propaganda, and its greedy, ravenous capitalism.

Flying (and Sailing) Home

When I read Toni Morrison, I often find myself haunted by the opening lines of William Butler Yeats’ “Second Coming,” a poem written early in his career: “Turning and turning in the widening gyre / The falcon cannot hear the falconer,” and the final lines from a poem he wrote at the end of his career, “The Circus Animal’s Desertion:” “Now that my ladder’s gone, / I must lie down where all the ladders start / In the foul rag-and-bone shop of the heart.” Even European poets have long evoked the gyre in mystical ways that fly (so to speak) in the face of rational history and linear time. Writing this, I find my mind again and again touch the lines from these European antecedents. But I’m also breathless about Morrison’s deployment of these rich symbols through their fusion with non-European forms, such as the African legend of “flying home.” Perhaps it is the rich ringed veins of poetry that travel around and unite the world, correcting for the dark grand narratives of history. Or maybe Audre Lorde put it best in “Poetry is Not a Luxury,” when she avers that

within structures defined by profit, by linear power, by institutional dehumanization, our feelings were not meant to survive. Kept around as unavoidable adjuncts or pleasant pastimes, feelings were meant to kneel to thought as [women] were meant to kneel to men. But women have survived. As poets… we have hidden [our pain and] our power. They lie in our dreams, and it is our dreams that point the way to freedom. They are made realizable through our poems that give us the strength and courage to see, to feel, to speak (37).

In my mind, Morrison’s novels are birds, circling in disquieted loops around the imperfect, ecstatic, guilty, loving, damaged human heart. They reject cant. They orbit a problem, a moment of rupture, and their circles avoid and then finally confront that rupture. Rather than a widening gyre, her gyres lead inward toward an exhumation of buried tragedy so that tragedy can be sun-smacked. Odysseus had Ithaka to which he could sail home and lay claim. Frank and Cee, denied that kind of homecoming, create their own internal home. Morrison pairs trauma theory with the traditional hero’s journey—and African mythologies as explored by Hinds specifically within Campbell’s template—to model a hybrid form of healing that runs against the grain of the American metanarrative. The Korean war backdrop dramatizes the double-trauma experienced by black soldiers in an integrated army who must return to a segregated America. And the structure of the novel is, in many ways, its primary argument: In using the frame of the testimonial, Morrison models a theory of trauma and recovery for all black Americans who live in a country that has mechanized the systematic erasure of their stories.

Works Cited

Campbell, Joseph. “The Monomyth” & “The Adventure of the Hero.” The Hero with a Thousand Faces, 3rd Edition, New World Library, 2008, pp. 1-74.

Herman, Judith Lewis. Trauma and Recovery: The Aftermath of Violence from Domestic Abuse to Political Terror. Perseus Books Group, 1997.

Hinds, Jay-Paul. “Flying Home: A Mode of Conversion in the African American Context.” Pastoral Psychology, Vol. 69, Issue 4, Aug 2020, pp. 383-404.

Lacan, Jacques. “Symbol and Language.” The Language of the Self. The Johns Hopkins U. Press, 1956.

Lorde, Audre. “Poetry is Not a Luxury.” Sister Outsider, The Crossing Press, 1993, pp. 36-9.

Lyotard, Jean-Francois. The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge. U. of Minnesota Press, 1979.

Montgomery, Maxine L. “Re-Membering the Forgotten War: Memory, History, and the Body in Toni Morrison’s Home.” CLA Journal, Vol. 55, No. 4, Jun 2012, pp. 320-334.

Morrison, Toni. Home. Vintage International, 2012.

Pease, Donald E. “The Uncanny Return of Settler-Colonial Capitalism in Toni Morrison’s Home.” Boundary 2, Vol 47, No. 2, 2020, pp. 49-70.

Tabone, Mark A. “Dystopia, Utopia, and ‘Home’ in Toni Morrison’s Home.” Utopian Studies, Vol. 29, No. 3, 2018, pp. 291-308.

Vissar, Irene. “Entanglements of Trauma: Relationality and Toni Morrison’s Home.” Postcolonial Text, Vol. 9, No. 2, 2014, pp. 1-21.

Yeats, William Butler. “The Second Coming” and “The Circus Animal’s Desertion.” The Collected Poems of W. B. Yeats, pp. 187, 346.