Ellipsis as the Unnamable in Thi Bui and Carmen Maria Machado

In “Memory and Narrative of Traumatic Events,” María Crespo and Violeta Fernández-Lansac explain the way trauma creates two discrete systems of memory that operate independently of and in parallel to one another. The first “comprises voluntary memories that are integrated with other autobiographical memories,” while the second contains “nonverbal information without a temporal context, whose access is automatic” (149). One system employs language and the other—received, involuntary, immediate—is silent. So how do memoir authors express aspects of trauma that are beyond speech? Thi Bui and Carmen Maria Machado, two unconventional memoirists who chronicle deeply scarring and politically-charged traumas, intentionally combine semiotic systems to give voice to memory’s silences. By weaving gaps and non-verbal expressions into their prose, they experientially represent the silence of second-tier traumatic memory. Bui combines textual and visual rhetoric in her graphic memoir The Best We Could Do, with spreads that let the gaps between the two semiotic systems express the hopes, fears, and uncertainties of immediate and involuntarily-experienced pain. Similarly, Machado’s In the Dream House layers its rhetorical structures: While the cracks in her text are marginally visual—in the form of experimentation with typography and form—her rhetorical breaks are primarily expressed in vertiginous genre shifts that recreate the instability of an abusive relationship. Both authors use narrative fracture, redoubling, and omission in the service of communicating the unnamable, and through these ellipses, they experientially render the unnamable disquiet of trauma.

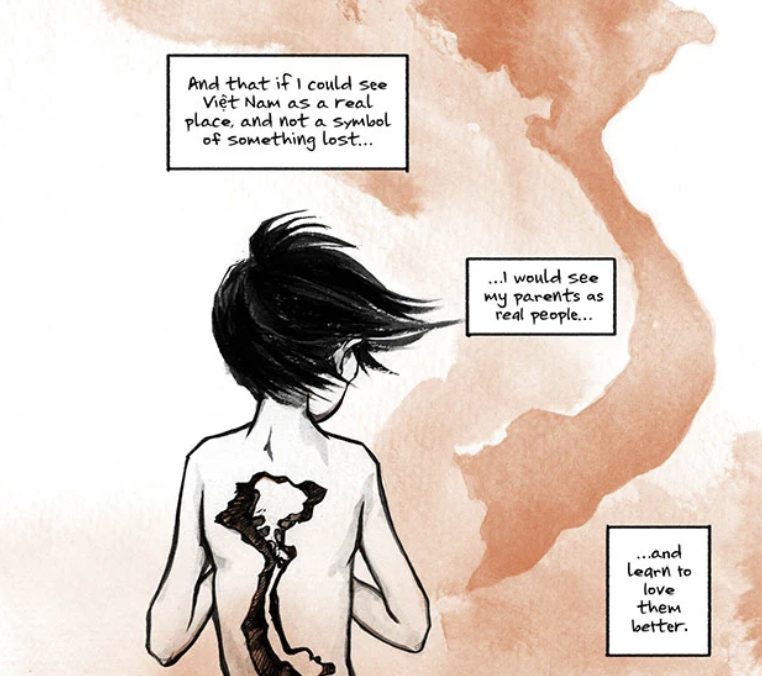

Bui’s graphic memoir chronicles her family’s traumatic journey from war-torn Viêt Nam to the United States, and the consequent hauntings of postmemory that affect two generations of Vietnamese immigrants. She blends words with panels of black and white line drawings, unified by a single-color wash in brick-red that places readers within the inexact, sepia-tones of memory. The words can be understood as Crespo and Fernández-Lansac’s first-order processed memories, while the images become the fragmentary memories of the second order. The red wash flows freely between words, images, and panels in a way that unifies disparate aspects of the same psyche. For example, in one spread Bui draws herself at a writing desk, beginning the project, enclosed in a panel. Behind her are ocean waves in the red-wash of memory, flowing into the page below. Beneath the panel is a young girl, her back turned to us, her hair blowing in the wind. She disappears off the bottom of the page in a full bleed, without a bounding box. On her back, a black tattoo of Viêt Nam, echoed by a mirror image of Viêt Nam in the wash in front of her. The words, in boxes, say “if I could see Viêt Nam as a real place, and not a symbol of something lost… I would see my parents as real people… and learn to love them better” (Bui 36). Through apposition, ellipses, and visual metaphor, the book places readers in the swell of traumatic memory: In the literal swell of memory, as the swells of the sea that transported her family on a tiny boat out of war-torn Viêt Nam are a recurring motif that expresses vulnerability, migration, and the tidal forces of women’s bodies.

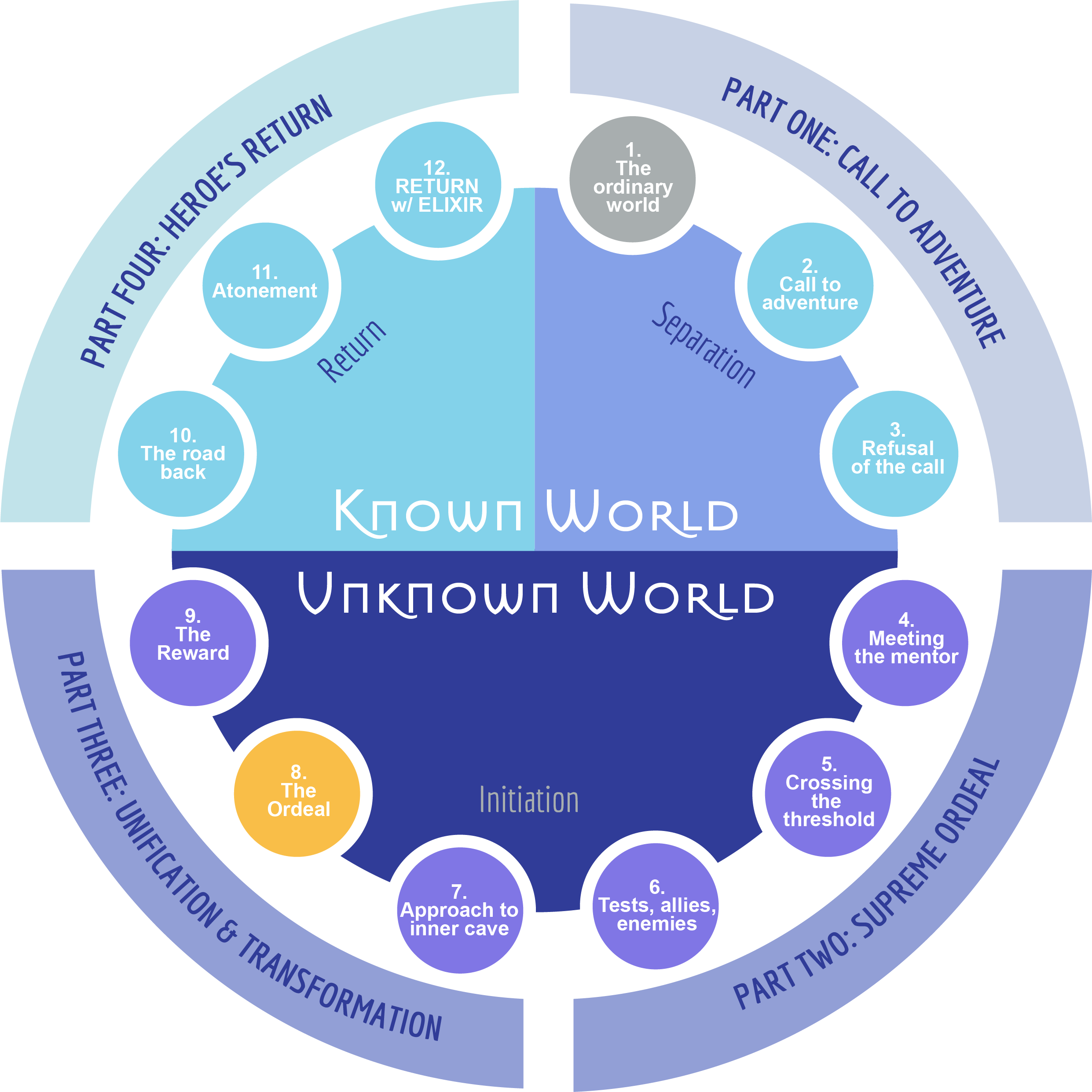

In Understanding Comics, Scott McCloud provides valuable insights about the multiple semiotic overlays that activate graphic literature. The gaps between panels, for instance, are known in comics scholarship as “the gutter”—the space where the action and events of the story are implied or suggested, but not fully shown or explained, and where readers are forced to commit “closure” (McCloud 63). Closure refers to the brain’s tendency to craft conceptual links between elements in apposition, even in instances where such links are not explicated by authors. As such, closure is necessarily experiential, asking the reader to, in a sense, co-author the story. It is the space where readers’ imaginations are activated, and where the significance and implications of the story are constructed. In the spread mentioned above, readers apprehend the images instantaneously: We see a writing woman bounded in a panel, which is linked, through closure and the red background unifying them, to a young girl with her home country written, in the form of a map, on her body. These images—which aren’t connected through reason but through emotion—slowly combine with words that explicitly link the pain of the country with the ongoing pain of the family until emotion, for the reader, squares with logic. The gutter plays a crucial role in mediating between sign systems in Bui’s text. McCloud discusses the way images are instantaneously “received” while words are “perceived,” a process that takes time, specialized knowledge, and the ability to de- and recode signs (49). The lag between reception and perception causes emotion and logic to harmonize at different registers. As such, the combination of word and image is perfect for rendering both first- and second-tier traumatic memories—the verbal and the scotomized or unnamable. By leaving space for the reader's imagination to fill in the gaps, Bui harnesses closure, the gutter, and the lag between reception and perception to weave a rich and complex narrative that is both conceptually coherent and emotionally wrenching.

Machado’s In the Dream House, too, forces readers to commit closure, though her methods are more conceptual than visual, including dizzying shifts in genre that occur each chapter. Her memoir chronicles same-sex intimate partner abuse, which readers co-experience in the narrative’s constant destabilizations, diversions, and repetitions. Machado writes sudden queasy shifts, violent mood swings, and pregnant ellipses into the text, subversions of narrative expectations that mirror the gaslighting, unpredictability, and cruelty of the relationship in question. While she does not exploit the split between received images and perceived text, she does manipulate our expectations of genre: Our anticipation of generic tropes, after all, precede cognition of the complex plot. Machado names her past abusive relationship “The Dream House,” and the unnamed girlfriend as “the Woman in the Dream House.” The narrative literally takes place in a small home in Bloomington Indiana in which the two lived during the author’s early twenties; but it figuratively takes place in an increasingly isolated and atemporal dreamscape that rollercoasters from erotic heights to horror-movie lows. We can read these different narrative layers as parallel to Bui’s overlay of words and images; and both authors use these unconventional techniques to layer Crespo and Fernández-Lansac’s first- and second-order memories. Machado employs second-person narration throughout. Readers come to understand that the author is the “I” at the time of writing, apostrophizing her former self, the one trapped in time, repeatedly and eternally undergoing abuse. Each chapter resituates the Dream House in a new genre, almost like switching the channels on a television, and the chapter titles, like “Dream House as Bildungsroman”; “Dream House as Haunted Mansion”; “Dream House as Cosmic Horror,” remain the only formal constant. Many of the chapters are short and impressionistic, sometimes as short as a single sentence, with connections to the narrative that are often oblique, tenuous, associative. Thus, much of the text is blank space. The interstices between Machado’s vignettes thereby function as “gutters” of sorts, that force readers to supply the connective tissue, like they must between the panels of Bui’s graphic memoir.

In “Exploring Same-Sex Female Intimate Partner Abuse Through Literary Tropes,” Sinéad Spelman notes that Machado endeavors to “bring to light invisible, and often taboo, areas of experience through stylistic experimentation,” in which the “the autobiographical first-person interrupt[s] dynamics of erasure and silencing” (45). Like Bui, Machado paradoxically uses silence to restore her own authority over a narrative that has been hijacked. Machado must walk a fine line to tell a story that has been commandeered both by the Woman in the Dream House on the one hand and by forces that are hostile to or essentializing of LGBTQ+ experiences on the other. The textual pauses between vignettes do a lot of work, forcing readers to participate in the text by committing closure where she leaves blank spaces. Take, for instance, the gap between “Dream House as Idiom” and “Dream House as Warning”: The final lines of the former contend that “Instead of a shared structure providing shelter, [‘safe as houses’] means that the person in charge is secure; everyone else should be afraid,” which yields immediately to “A few months before your girlfriend became the Woman in the Dream House, a young… undergrad went missing in Bloomington” (Machado 78-9). While the observation about the idiom “safe as houses” and the young missing girl are literally unrelated, they are figuratively tied together, and readers cannot help but link them through closure. Thus, as happens in the ellipses between all of the vignettes—indeed one could almost take any two contiguous vignettes to make the same point—the two ideas grow together, such that even the joy of moving in with a lover becomes tinged with threat. The author is not “safe as houses” in the Dream House, since she is implicitly not the one in charge, and then she becomes the missing girl, who, it is implied, has been disappeared by a perpetrator. This perpetrator, our brains tell us, illogically, is the Woman in the Dream House.

Both authors aestheticize eloquent silences. Jacques Derrida offers insights about the deep resonances of silence. In “Ellipsis,” he notes that what is left out of texts, the absences or “ellipses,” “redouble and consecrate” the words that remain (296). Pauses pepper Bui’s and Machado’s texts, stylistically and rhetorically, and Derrida’s conception of the ellipsis helps to ground their semiotically unstable methods. Textual blind spots, he argues, contain a “fabric of traces” for readers to decode, for “all meaning is altered by this lack” (Derrida 296). By “pronouncing non-closure,” Derrida maintains, the gaps are both “infinitely open and infinitely reflecting on [themselves]” in a Möbius strip that “redoubles” meaning. Redoubling, to Derrida, disrupts the traditional hierarchy of language, highlighting its inherent instability and ambiguity (Derrida 298). Bui and Machado use negative space as a kind of redoubling, creating the outlines of trauma such that the shape of its impact is clear, even if it cannot be looked at directly. Since they are both women whose identities are already marginalized by factors other than their trauma, they use gaps to forestall the external suppression of the traumatic experiences that further marginalize them. In an interview with Aaron Burkhalter, Bui discusses cultural silence: “my people speak in pregnant silences and don't argue. So I had to figure out how to do that in comics. It turns out that comics are actually good at showing silences.” McCloud discusses the emotional impact of silence in comics; the way silences push content into eternal and unchanging spaces, remarking,

the content of a silent panel… can produce a sense of timelessness. Because of its unresolved nature, such a panel may linger in the readers’ mind… When ‘bleeds’ are used, time is no longer contained, but instead hemorrhages and escapes into timeless space. (102)

We might look once more at Bui’s older version of herself sitting inside the panel, imagining the full-bleed image of her younger self below. The self below is trapped in timeless space, even as the author ages. This, according to Crespo and Fernández-Lansac, is how second-tier trauma memories work: “Triggered by perceptual cues,” they are “dominated by vivid sensorial details” that fragment and arrest time (149). These involuntary memories return the afflicted person against and again back to the site and conditions of the trauma. In an interview with Madi Haslam, Machado, too, discusses her aesthetic choice to use second person as a negotiation between her older self and the younger self who is doomed, when triggered by external stimuli, to repeat the traumatic memory:

I talk about this first-person Carmen—that's me—and the second-person Carmen—that's like this past version of myself that can't access any of the knowledge that I have… she is constantly turning on this hamster wheel of pain, trapped in the past… She’s stuck there forever and there's nothing I can do about it, so [using second person is] sort of honoring that wall.

Thi Bui

By taking control, visiting the scenes of trauma on their own terms, these authors perform a kind of healing scriptotherapy, which Sidonie Smith and Julia Watson, in Reading Autobiography, refer to as “the process of speaking or writing about trauma in order to find words to give voice to previously repressed memories” (29). Both Bui and Machado create, gaze at, and empathize with these remembered selves who cannot speak, who are immobile within the amber of their distress. Both authors use silence to sanctify their timeless, full-bleed suffering.

Derrida conceives of the ellipsis as a tool to draw readers’ attention to what is missing in a text, suggesting there is always more to be said or thought in these textual gaps. Ellipses, being circular and recursive in nature, as well as pregnant with potential energy, challenge a linear philosophical telos. They open new, more rhizomatic structures of thought around familiar ideas as a part of Derrida’s broader project of deconstruction, which seeks to expose the hidden assumptions and biases that buttress Western epistemology. Both Bui and Machado are women of color with a specific positionality within mainstream culture, and thus their narratives are triply adulterated by the strains of dominant discourse: They are women on one hand; they are women of color on another; and finally, Bui is an immigrant and Machado is from the LGBTQ+ community. While everyone suffering unnamable trauma works within some form of narrative mediation that they must navigate and, if necessary, dismantle, immigrants and queer women of color must kick against tremendous undercurrents to be heard at all. Moreover, they are burdened with representing not only themselves but an entire category of people, balancing personal truth with the need to protect their group from harmful stereotypes. Ellipses can help, strategic silences that speak a language that is different from but complementary to the narrative. Through the differences between word and image for Bui and between a first-person narrator and a second-person self in Machado, these two women navigate memories that do not square with, or that fit uncomfortably among, existing narratives about immigrants and queer people.

The Viêt Nam war, for instance, has deeply entrenched narratives in the United States, and part of Bui’s project is redressing the “stereotypes and terrible cliches about Vietnamese people from bad Vietnam War movies” (Burkhalter). And so she must fight against calcified history in writing her historically-specific trauma. As Stella Oh observes in “Birthing a Graphic Archive of Memory: Re-Viewing the Refugee Experience in Thi Bui’s The Best We Could Do,”

Rather than dehistoricizing trauma, Bui positions trauma and the material conditions of war firmly and literally on the back of the character and engages in a political project of recuperative narrativization. The graphic novel serves as a form of cartography, mapping our ways of perceiving Vietnam and the Vietnamese War in spatial and recursive modes that intervene in dominant tropes of Vietnam and representations of the war. (81)

Carmen Maria Machado

Like Bui, Machado expresses frustration that the legal and social narratives about queer people make her leery of representing the Woman in the Dream House as “the specter of the lunatic lesbian” (126), but she is compelled to write her experience because “the nature of archival silence is that certain people’s narratives and their nuances are swallowed by history” (138). Being in the double-bind of trauma on the one hand and cultural invisibility on the other compels both women to aestheticize silence, if only to keep their narratives out of the greedy grasp of pre-existing and limiting white Western heteronormative thought. God, as the old saying goes, can be glimpsed right there in the gaps.

In sum, ellipses run like electrical currents through both authors’ prose, and their texts use ellipses to explore trauma by mixing semiotic systems, in ways that correspond to Crespo and Fernández-Lansac’s two tiers of traumatic memory. Machado and Bui employ writerly techniques that, through silence, become powerful archives of traumatic memory and postmemory. Kelly Hurley’s “Trauma and Horror” argues that traditional modes of narration such as realism are inadequate for the abreaction of trauma, because it isn’t possible to render

a “true” representation of traumatic events, given that the very experience of trauma involves the derangement, even the shattering, of the subjective apparatus designed to process it. Traumatic events can only be understood belatedly and imperfectly; they give rise to repetitive dreams and uncontrollable flashbacks and generate this-is-what-happened stories characterized by disjunction and distortion. (2)

Bui and Machado’s grapplings thereby provide models of healing that acknowledge and honor breakages and fractures, sanctifying the gap between what can be spoken and what exists beyond words. Their fractured narratives, rather than smoothing over the jagged edges of trauma, choose to aestheticize the breakages as a way to honor their experiences and experientially convey them to readers. Both of them are doing something that becomes a source of empowerment for those who find their experiences outside of accepted reality: They queer the pitch, semiotically, a tactic that strikes me as a kind of écriture féminine, since women, when it comes to trauma, often have to fight tooth and claw to wrest their stories back from a dehumanizing hegemony that would prefer to smooth out, simplify, or simply erase their story from the archive.

Works Cited

Burkhalter, Aaron. “Thi Bui Brings Her Graphic Novel Memoir to Seattle for Four Days of Appearances.” The South Seattle Emerald, 8 April 2019.

Crespo, María and Violeta Fernández-Lansac. “Memory and Narrative of Traumatic Events: A Literature Review.” Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 2016, Vol. 8, No. 2, pp. 149–156.

Derrida, Jacques. “Ellipsis.” Writing and Difference. Translated by Alan Bass, U. of Chicago P., 1978, pp. 294-300.

Haslam, Madi. “The House is a Space of Living Metaphor: An Interview with Carmen Maria Machado.” MaisonNeuve, 20 Dec. 2019, Accessed 10 Dec 2022.

Hurley, Kelly. “Trauma and Horror: Anguish and Transfiguration.” English language Notes, Vol. 59, No. 2, Oct. 2021, pp. 2-8.

McCloud, Scott. Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. HarperCollins Publishing, 1993.

Oh, Stella. “Birthing a Graphic Archive of Memory: Re-Viewing the Refugee Experience in Thi Bui’s The Best We Could Do.” Melus, Vol 25, No. 4, Winter 2020, pp. 72-90.

Smith, Sidonie and Julia Watson. Reading Autobiography: A Guide for Interpreting Life Narratives, Second Edition. U. of Minnesota P., 2010.

Spelman, Sinéad. “Carmen Maria Machado's Memoir In The Dream House: Exploring Same-Sex Female Intimate Partner Abuse Through Literary Tropes.” Journal of Gender, Globalisation and Rights, No. 3, 2022.