The Family and the Polis in Aeschylus’ Oresteia

In Aeschylus’ Oresteia, marriage is war. In a literal rather than a metaphorical sense: The perversion of the marriages of Atreus, Menelaus, and Agamemnon form a chain of iniquity that leads directly to the Trojan War and its tragical aftermath, and the text links the failure of blood ties to the failure of the state. But the sacrifice of young unmarried women in the play—whom the text renders as especially tragic—is what delays and complicates the carrying out of justice. Or, rather, it sets one paradigm of divine justice against another, equally important one. Cassandra is one such Parthenos, and her fruitless prophesizing transforms her into a crucial audience surrogate: Like us, she is armed with foreknowledge about how the play’s action will transpire but (like us) she is unable to use her knowledge to change events and is doomed to watch them unfold with the same combination of pity and terror that the audience experiences. A figure of impossible duality, she is at once nubile and doubly-wed; at once princess and slave; and, most crucially, at once herself and an echo of another Parthenos, the unjustly sacrificed Iphigenia. She cannot be suffered to survive this duality, but without such recursion in Cassandra’s body, the story cannot be suffered to survive. In her, the plays’ warring energies collide: Cold, rational Apollo, overseer of masculine order, and the hot, feminine temper of the Furies. It takes a divine arbiter in the form of Athena to settle the dispute between the justice of the Polis and the justice of the home, and to restore equilibrium to the chaos created by the drama’s many perversions of marriage.

Cassandra personifies the state that has captured her. Like the ruling family of Argos, her life is defined—and defiled—by a curse. The curse on the house of Atreus, Aeschylus makes clear, was initiated when Atreus’ brother Thyestes seduced his wife in a prior generation. In revenge, Atreus fed Thyestes his own children. Cassandra, the play’s truth-teller, renders this curse legible for the audience when she characterizes her new home as “A house that hates the gods, a houses in / on the wicked murder of its own, of itself, a house full of nooses” and she gets more explicit when she references “the babies wailing over the sacrifice, / and the roasted meat on which their father was fed” (Ag. 1090-1, 1096-7). This initial horror—the first mutilation of marriage and child-rearing bonds—has, by the time of the action, rippled out to subsequent generations such that the curse dooms the entire culture to violent instability. Menelaus drags his allies into the protracted Trojan war because of the abduction of his wife by her lover, Paris; Agamemnon sacrifices his daughter Iphigenia in exchange for favorable sailing winds. In “The Marriage of Cassandra and the Oresteia,” Robin Mitchell-Boyask notes that “the color of Iphigenia's robes, ‘saffron-dyed’… suggests the appearance of the Greek bridal veil,” and thus we see that she, thinking she would be wed, was sacrificed instead (283). In turn, Agamemnon’s wife, Clytemnestra, takes ferocious revenge for Iphigenia’s murder upon her husband’s return from the Trojan War, killing him in the bath. From there, their son, Orestes, must obey Apollo by murdering his own mother in retribution for the regicide. Though that is the last human death, Orestes is so hounded by the Furies—the fierce, ancient deities who preside over kinship bonds—that he is driven mad, unable to ascend to his father’s throne. No human recourse can interrupt the endless cycle of bloodshed and suffering ensured by the curse.

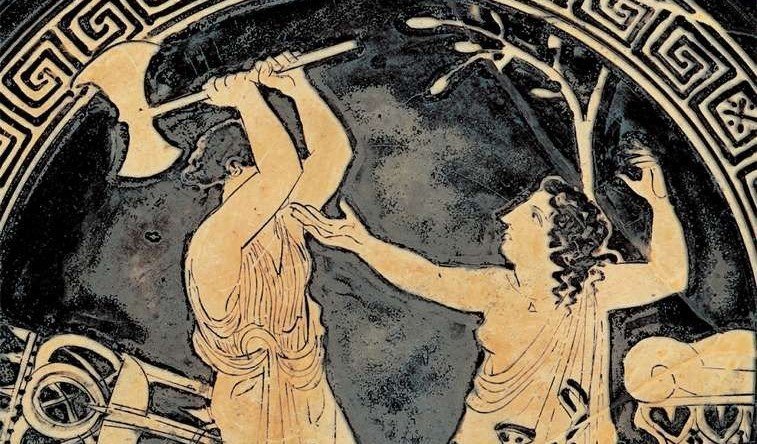

In parallel to the curse on the house of Atreus, Cassandra suffers under her own curse. Apollo, at some point in the past, gave her the wooing gift of foresight, but when she spurned him, he cursed her by ensuring her prophecies would never be believed. When we meet her, she is a war prize bequeathed to Agamemnon by his army, a former princess of the conquered Troy, now a slave. A Parthenos, Cassandra must follow Agamemnon into his home in a caricature of Greek marriage rites, which, as Mitchell-Boyask notes, “cast the bride’s departure from her house as an abduction and then death” (276). By tradition, a bride is delivered by chariot from her mother’s to her mother-in-law’s household, an act that is “strongly associated with the Persephone myth that this drama evokes” (Mitchell-Boyask 276). So marriage—a girl’s forced obeisance to a new lord—is framed as a kind of death. When Cassandra arrives in Argos as war booty, the play’s staging casts her as his bride, alighting from a chariot while he marches on foot, and his wife, Clytemnestra, becomes a stand-in for her mother-in-law, greeting her at the door. The bride imagery, however, is redoubled by her entreaties to Apollo, whose bride, we learn, she should also be. The saffron of Iphigenia’s robes is reiterated in the text by the chorus, who liken the chill her words have on their blood as “the color of men who have fallen / in battle and lie in the rays of their life as it sets” (Ag. 1121-3). Though Mary Lefkowitz’ translation alludes to Apollo in evoking the color of sunbeams—he is after all the god of sunlight and patron of young ephebes in the military—Mitchell-Boyask translates the line as “saffron-dyed blood” (283). This textual echo strikes me as critical in generating a resonance between the plays’ two Parthenoi. Doubly a bride, Cassandra is no bride at all. She laments, “No father’s altar waits there, but a block— / scarlet and warm when I’m the sacrifice,” strengthening her link to Iphigenia (Ag. 1277-8). Death is her last resort, and the only way to consummate the aborted wedding to Apollo. Mitchell-Boyask notes the way Cassandra’s lot becomes metonymy for the state:

By presenting Cassandra as Apollo's bride the dramatist looks forward and prepares his audience for important aspects of the next two parts of the trilogy, including the role of Orestes as a maturing ephebe claiming his patrimony under Apollo's guidance and Apollo's extremely problematic… conduct during Orestes's trial. (271)

Through Cassandra, the play intimates that intuition cannot comfortably mate with rationality: There is no perfect union possible between rational and intuitive justice. A balance must be struck between the ancient Furies and the younger gods of the Polis if there is to be any dramatic resolution. Once inside the home, Cassandra removes her veil with the words “I’ll prophesy no longer like a new bride / timidly peering out beneath her veil” (Ag. 1178-9). Mitchell-Boyask asserts that “Her progress into clarity here, lifting the veil, stands for her as the consummation of her marriage as it accompanies her accession to death as a Bride of Apollo” (278). Cassandra can fulfill her obligation to Apollo only through death, and thus serves as a recursion of the fatal conflict between sign systems that the culture suffers: It takes a balance of the feminine and masculine principles, embodied by Athena, to provide a resolution, albeit an imperfect one.

When Apollo tells Orestes to travel to Athens to be tried by the courts, he informs us that the city’s patron goddess, Athena, will adjudicate the proceedings. This represents a yielding of ancient custom—clan justice with its cycles of never-ending carnage—to the urbane laws of the Polis. No human character in the trilogy is wise to condemn of defy Apollo, but Aeschylus does not present him as just or trustworthy either. His system of marshal justice, too, is proven insufficient, and the play demonstrates that Athens’ civic legal code is equipped to recognize and contend with such insufficiencies. Apollo serves, in the trial, as the god for the defense, and he begins inauspiciously by insulting the Furies, who are serving as the jury. He arrogantly demands that they leave the Areopagus, saying: “You should share a cave / with a blood-guzzling lion, and not wipe / your dirt on others at this oracle. / You strays, you feral goats, move off!” (Eu. 193-6). Athena, though she rules in favor of Apollo and Orestes, serves as diplomat, calming, negotiating with, and expressing reverence for the Furies so that all sides are more or less satisfied with the outcome. As a goddess begotten of Zeus’ forehead, she represents both male and female principles, announcing herself as mediator between their interests with these words:

There is no mother who gave birth to me.

With all my heart, I hold with what is male—

except through marriage. I am all my father’s,

no partisan of any woman killed

for murdering her husband, her home’s watchman. (Eu. 736-40)

The Furies are angered by Apollo, but Athena turns to them with the words “let me persuade you” (Eu. 793). She promotes them, promising them the privilege and worship due to goddesses, for “No household here could thrive apart from you” (Eu. 896). It takes a woman (Athena) to reconcile the fierceness of a lioness protecting a cub (Clytemnestra) with the impartial justice of the state (Apollo). Thus, the trilogy’s conclusion makes plain the theme of incompatible systems of justice, models a resolution to the incompatibility, and delivers Cassandra and Iphigenia vengeance, paltry but satisfactory.

Cassandra and her antecedent are keystones that communicate the trilogy’s gendered orientation to justice. The drama subtly suggests that an all-male justice schema will catch too many innocents in its crossfire. Feminine interests in the drama are represented by fabrics, as exemplified by Iphigenia’s saffron robe; Cassandra’s bridal/prophetic veil; and, as yet unmentioned, the tapestries spread out by Clytemnestra upon Agamemnon’s return. Clytemnestra welcomes him home by spreading sumptuous textiles beneath his feet. They are dyed with precious murex, too fine to be walked on, and she does it as a kind of test. Agamemnon at first demurs, saying only gods should trample such fabrics, but his ego eventually cannot hold up to the temptation, and he treads on them. This act of male hubris signals that Agamemnon has failed his wife’s test. But he also fails ours: Even after sacrificing countless soldiers in a long and bloody war, he is still willing to tread on something fine to serve himself, the way he tread on his daughter by sacrificing her to his own glory. Apollo oversees and adjudges young ephebes, and as such he is a god with a connection to the justice of war—a god whose sister demanded Iphigenia’s blood sacrifice. But he is also himself without a consort, and is thus a threat to young parthenoi, as much as human ephebes are, which we learn from his menacing of Cassandra; and from the Furies, toward whom his behavior is unforgivable. The justice of women, however, based on rage and instinct, while understandable, is also insufficient to run the state, as we see in the curse that the Furies have unleashed on the house of Atreus. Setting aside the gendered aspect of the systems of justice, the metaphor of Cassandra is as useful today as it presumably was in the time of Aeschylus. We still do not have a perfect system of justice; and we still struggle for grace and balance under the law. These plays go deeply and psychomachically into the psychology of ethics, wherein one aspect of human experience doesn’t “play nice” with other aspects. Many if not all, at times, experience the pride and hubris of Agamemnon; the rage and vengeance of Clytemnestra; the impossible choices and hounding conscience of Orestes. Many of us struggle, at the personal, familial, and state levels, to restore order and equilibrium to a kingdom that is perpetually torn asunder.

Works Cited

Aeschylus. “The Oresteia.” The Greek Plays: Sixteen Plays by Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides, Translated by Mary Lefkowitz and James Romm, Modern Library, 2017, pp. 51-177.

Mitchell-Boyask, Robin. “The Marriage of Cassandra and the ‘Oresteia’: Text, Image, Performance.” The American Philological Association, Vol. 136, No. 2, Autumn 2006, pp. 269-97.